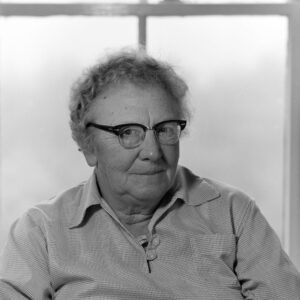

Ruth Moore was a popular American mid-century novelist. William Morrow released her debut novel, The Wier, in 1943, and it was well-received by critics. Her follow-up, Spoonhandle (1946), spent 16 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. Twentieth Century Fox bought the film rights and released it as Deep Waters in 1948. The movie was directed by Henry King and starred Dana Andrews and Jean Peters.

Contemporary critics praised her for her honest portrayals of Maine people and evocative descriptions of the state. Her name was mentioned in the same breath as William Faulkner.

Eventually, Moore’s national popularity declined. Her early novels were often selected as Book of the Month Club picks. She published fourteen novels and three collections of poetry. William Morrow released her final novel, Sarah Walked Over the Mountain, in 1979. She was regarded as a writer “popular with housewives.” At a time when male critics often looked down upon and dismissed the work of female authors, the preferences of female readers were even less valued.

Moore is now known as a regional writer, a descriptor she fought during her career.

“She was a regional writer only in the sense that one could call Faulkner regional, as he wrote of his ‘postage stamp of soil.’ Both writers had the gift of capturing the universal in the local… A novel about New York City or Chicago is always about New York City or Chicago, while a novel about Maine or Jefferson, Mississippi, in skilled hands, could be about any place in the world.” -Sven Davisson, introduction to The Day Foley Craddock Tore off My Grandfather’s Thumb

In a rare 1988 interview, Moore herself noted, “If you’re writing about Maine; you’re writing about anywhere.”

Moore is now widely considered among the most significant Maine authors of the 20th century. Her work has survived the test of time, and her books have remained continuously in print. Her themes of economic and social stress in small Maine towns remain relevant. Her skillful use of vernacular has aged well and avoided the devolvement into painful “quaintness” of other writers attempting to capture regional accents.

Moore was forty when her first novel was released. When asked what had taken her so long, she replied, “I was busy living.”

While compiling her biography, I discovered a resume in the University of New England’s Maine Women’s Writers Archive. Moore outlines her work history from 1926 to 1941, as is typical for such documents. In 1926, she relocated from Maine to Greenwich Village to take a position as private secretary to Mary White Ovington, one of the founders and the first leader of the NAACP. The Ovington family were summer residents with a house on the island where Moore grew up. The following year, she secured a job with the NAACP itself. Before long, she advanced to the role of campaign manager, reporting directly to the then-head, James Weldon Johnson. Johnson was a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance and penned the hymn “Lift Every Voice and Sing” adopted as the Black National Anthem.

At the time, a curious entry details months spent as a special investigator for the organization. This work, she notes, necessitated “extensive” travel through the South in the spring of 1929. She gives only slight clues that the case involved two black youths wrongly accused of murder.

In a 1947 interview, she recounted the episode to the Portland Sunday Telegram: “But I was anything but a trained detective, and I suppose I didn’t keep my investigations very secret. People were nasty and I was finally ordered to leave town.”

Learning more about this period was one of the significant obstacles in my research journey. That was the case until a couple of winters ago when I received an unexpected email from Dr. John Kirk, Director of the Anderson Institute on Race and Ethnicity and History at the University of Arkansas. His graduate class was investigating the late twenties cases of Robert Bell and Grady Swain. In his search for “Ruth Moore” referenced in the NAACP case file, he stumbled upon some of my biographical work. He then shared with me the 15-page report Moore had submitted following her work.

In early April 1929, she traveled to Mobile, posing as a New York reporter covering a story on farm relief. She attempted to reach Greasy Corner, Arkansas, where the case had unfolded, but was thwarted by spring floodwaters. However, she managed to speak with several key figures in the case, including defense attorneys and locals sympathetic to the boys. Eventually, she was warned that it would be best for her to leave town. At the time, Ruth was just shy of her 26th birthday. She told me she had been chosen for the work because a woman was thought to be less likely to be harmed. Investigating lynching, riots, and race-based violence in the American South was inherently dangerous work.

Except from the NAACP Case File:

I hired a Ford with an old colored man to drive it, and started out over country roads in the general direction of Greasy Corner. It was not very companionable, my chauffeur sat solitary in the front seat and I very solitary in the back. He did not believe we would be able to drive very far. Experience had made him a pessimist.

Rain the night before had filled the roads with deep puddles, and most of these puddles were camouflage for “chug-holes”. A. chug-hole is a sort of honey-pot in the road, which either looks bottomless and is two inches deep, or looks two inches deep and is bottomless. My driver’s method was to stop before each one and wade ahead to poke into it with a stick. If he struck bottom with the first few pokes, we went ahead; if not, we laid down a pair of planks which we carried on the running board and drove over them. About eight miles from town we came upon the king of all chug-holes, or rather, a creek flowing across the road. We put down the planks and drove on them before they had time to float away; but they were not quite long enough, Water came through the floor of the Ford and must have reached the ignition. The engine died, and there we settled down.

My driver remarked that he reckoned we’d need a mule. There was a cabin in the middle of a field about a mile away, and while he went splashing across to see if the people owned a mule, I sat on top of the Ford and listened to the water. I might have fished, but I had no pole. He came back presently and said that those folks in the cabin had all gone away. We’d just have to wait until somebody came along.

“Is it likely anyone will?” I asked him.

“Ah cain’t say,” he answered, “but Ah ain’ reckonin’ on it.”

“I’ll tell you,” said I, “you carry me ashore and I’ll start walking back.”

He shook his head hard. “No, mam! Ah ain’ puttin’ mah han’s on no white lady.”

“Oh, don’t be foolish,” said I. “Make believe you’re saving my life. There’s no one around, and I’ve got to yet ashore somehow.”

“Ah knows that,” said he, “But spos’n there was?”

And so I pulled off my shoes and stockings and waded out, and set off toward the town very much out of patience with the customs of the country.

After a long time, a farmer on a mule-wagon offered me a lift, but I discovered I could walk faster than the mule and stayed with him only long enough to rest. I missed the road once, and so it was very late and dark when I got back to my room in the town. The restaurants were all closed, but my landlady gave me some bread and ham and a glass of milk. I was too tired to eat much, however, and left some of the food lying on a chair. Towards morning I was wakened by a large rat running over me, and discovered four others making merry on the floor. I threw at them three hard, round pincushions which were on the bureau, and after a time, went to sleep again.

The next morning a young man in muddy leggins asked my business and warned me to leave town. He would not say why. He seemed to know what I was after, though he did not say so directly…

Despite Moore’s efforts to investigate and gather information, the social and legal barriers of the era hindered any meaningful progress toward justice for the boys. The case was overturned on appeal and returned to the lower court. Eventually in March 1930, the judge offered the two young men a plea-deal that would take into account time served and ostensibly involve under two years additional prison time. Unfortunately for the two, the parole board ignored the judge’s deal and repeatedly denied them release. The boys were finally released as a result of executive action by the governor in September 1935.

The cases of Bell and Swain highlighted the pervasive racial injustices of the time. Both young Black men were wrongfully accused of murder and sentenced to death by the electric chair. These cases exemplified the systemic racism entrenched in the legal system and the societal pressures that often dictated the outcomes for African Americans in the South. Ruth Moore’s involvement as a special investigator for the NAACP during this turbulent period underscored the challenges faced by those who dared to confront racial discrimination and fight for justice. Ultimately, the wrongful accusations against Bell and Swain illuminated the urgent need for legal reform and greater public awareness regarding the civil rights of all individuals, regardless of race.

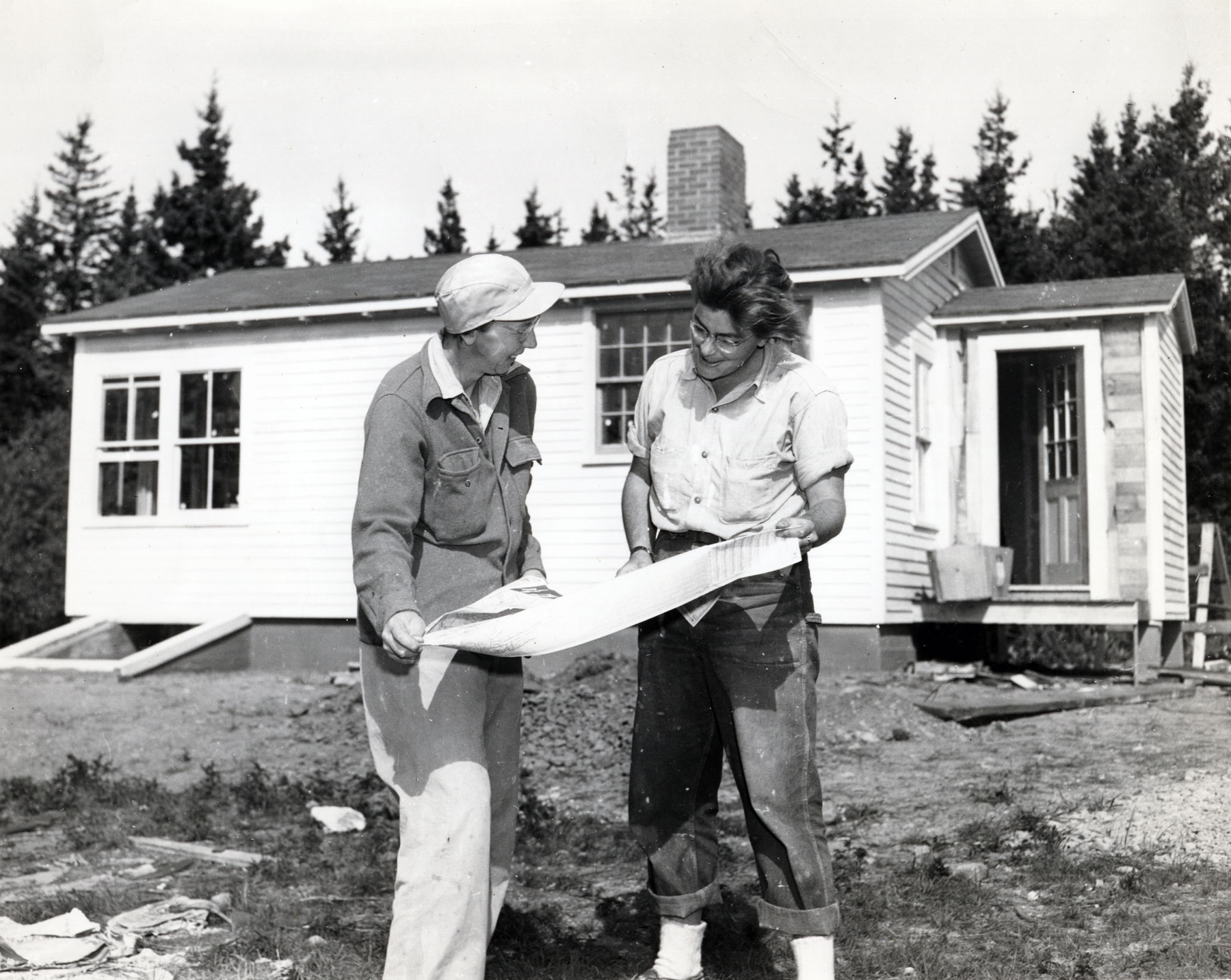

After her time with the NAACP, she worked for the liberal minister John Haynes Holmes and later for the novelist Alice Tisdale Hobart. Eventually, she took over the management of Hobart’s nut ranch in California. While at home one summer in the early forties, she met Eleanor Mayo. The two remained together until Mayo’s death from a brain tumor in 1981.

Moore studied economics, and this, along with her experience with progressive activism, undoubtedly informed her work. Spoonhandle is likely the first significant representation of Black characters in a Maine novel.

For her own part, Mayo published five novels, one of which was made into the B-film noir Tarnished. In the 1950s, the Maine press noted her as the first woman elected “selectman” in the town of Tremont.

Moore used the proceeds from Deep Waters to buy land in Maine, and the two built a house together in 1947. This provoked the press to dub the pair the “Lady Carpenters.” The house became a frequent gathering place for female couples, including painter Chenoweth Hall and her partner, author Miriam Caldwell, from nearby Prospect Harbor. Due to Moore’s significance to literature, the house is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

I am currently working on a biography of the lives of Moore and Mayo, compiling their own words and drawing from hundreds of letters, journals, and interviews. Their short fiction, which I edited, was released by Blackberry Books as The Day Foley Craddock Tore Off my Grandfather’s Thumb, marking the first time they appeared in print together.

Islandport Press is currently reprinting Moore’s books. Rebel Satori has re-issued five of Mayo’s novels and will release a collection of her photography soon. Two unpublished Mayo manuscripts are also in development.

Sven Davisson

Rebel Satori Publisher